This article was written by our team member Bisila, for the digital magazine History Workshop after our first Black Herstory Workshops in October 2016.

In an interview some years ago, African-American actor Morgan Freeman said that he did not want a Black History Month. Since ‘black history is American history’, he argued, we should stop referring to black people as ‘black people’ and stop calling white people ‘white people’. Let’s call each other by our names. Let’s all just be people. No adjectives.

It’s a pertinent (and hopeful) remark, but it’s not yet time to stop recognising black history and black people. The sad truth is that black history has long been omitted from the history, from our national identity — at least in the United Kingdom, and especially when it comes to women. Therefore, events like Black History Month offer us the opportunity to turn the spotlight on the black community, its culture, traditions and achievements and make them accessible to the general public.

At Lon-art, we have been organising educational workshops and community events since 2010 in order to promote culture, languages and art. We put gender equality at the very core of our work. If being a woman can still be rather tricky nowadays, being a black woman makes things a tad more ‘interesting’. We tend to lump all women together when talking about women’s struggles and forget to think about intersectionality. This means that we need to recognise how different identities or groups experience the world differently, even if they are all women. It is crucial that we properly address and acknowledge their different experiences and issues. And so, for this year’s Black History Month celebrations in the London borough of Tower Hamlets, Lon-art decided to run workshops about black women’s history.

When we started designing the workshops, we realised that, if historical references to women in general are fairly scarce, acknowledgement of black women’s contributions are virtually non-existent —even for those women who contributed significantly to British society. Too often, history only remembers great discoveries and deeds. There are many people, however, who dedicated their lives to others. Their contributions may have been on a smaller or more local scale, but they also shaped this country. We believe those women and their stories should also be remembered and given the recognition they deserve.

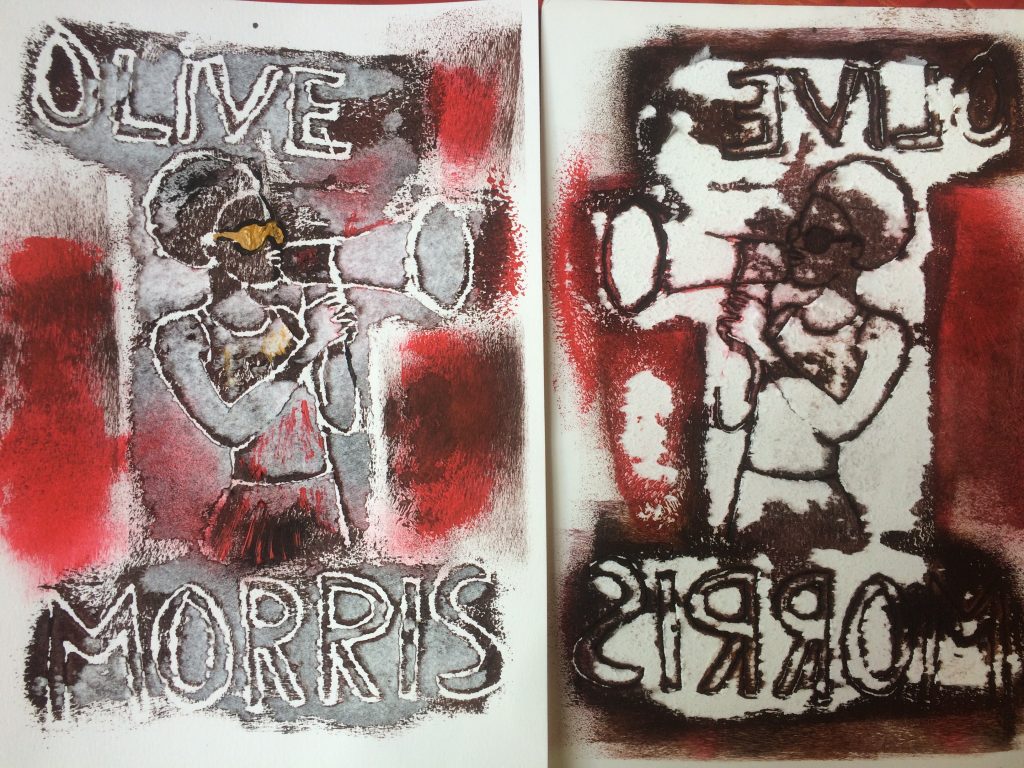

Let’s start with someone like Olive Morris, an activist who carried out her first conscious political act when she was only 17 years old. Until she died of cancer aged 27 in 1979 she relentlessly fought for equality. She was one of the leaders of the Black Panther movement in Brixton. She joined and also set up numerous organisations to educate and empower the black community both in London and Manchester. These include the Brixton Black Women’s Group, the Manchester Black Women’s Co-operative and the Black Women’s Mutual Aid Group, The Organisation of Women of Asian and African Descent and the Sarbarr Bookshop, the first Black self-help community bookshop in south London. Morris dedicated much of her work to black women. Even though she was young, her activism helped pioneer an intersectional approach already in the 1970s, something which we could still learn from today.

There is also Claudia Jones, civil rights activist, journalist and founder of the West Indian Gazette, or WIG, the first major newspaper for the black community in the UK. In 1959, one year after she started the WIG, she organised a ‘Caribbean Carnival’ at the St Pancras town hall. Her aim was to create a fresh start in the aftermath of the UK’s first widespread racial conflict – the Notting Hill and Nottingham riots. The event, which was broadcast by the BBC, inspired the Notting Hill Carnival.

And we could not forget Mary Seacole, whose name is becoming more widely known following the success of 12 years of campaigning by the Mary Seacole Memorial Statue Appeal. In 1855 – a year after the Crimean War broke out – Seacole travelled from Jamaica to London to offer her services as a nurse working with Florence Nightingale. Despite references proving her skills, her offer was rejected. Nevertheless, she persevered against discrimination, collected funds to travel to Crimea and, once there, opened the British Hotel to provide soldiers with food and nursing care.

The contributions and historical significance of black women like these have been largely forgotten in the United Kingdom.

In London, neighbourhood institutions and small organisations alike work together to keep black history alive, including Black History Studies, the Bernie Grant Arts Centre in Tottenham or the Black Cultural Archives in Brixton. Their work is crucial. So too is the work that national institutions and museums should be contributing to making these stories accessible to the wider public. Without those efforts, these histories will never be included in our national story.

We have learnt at Lon-art that the elite – that is, generally, white men – have too often decided what achievements are recorded in the annals of our national history. Whatever black women have achieved is rarely considered relevant. Consequently, it has been, and still is, difficult for younger generations of black children, especially girls, to imagine their own future successes on this scale. Without role models to look up to, historic forbears to emulate, they are left without examples of success to identify with.

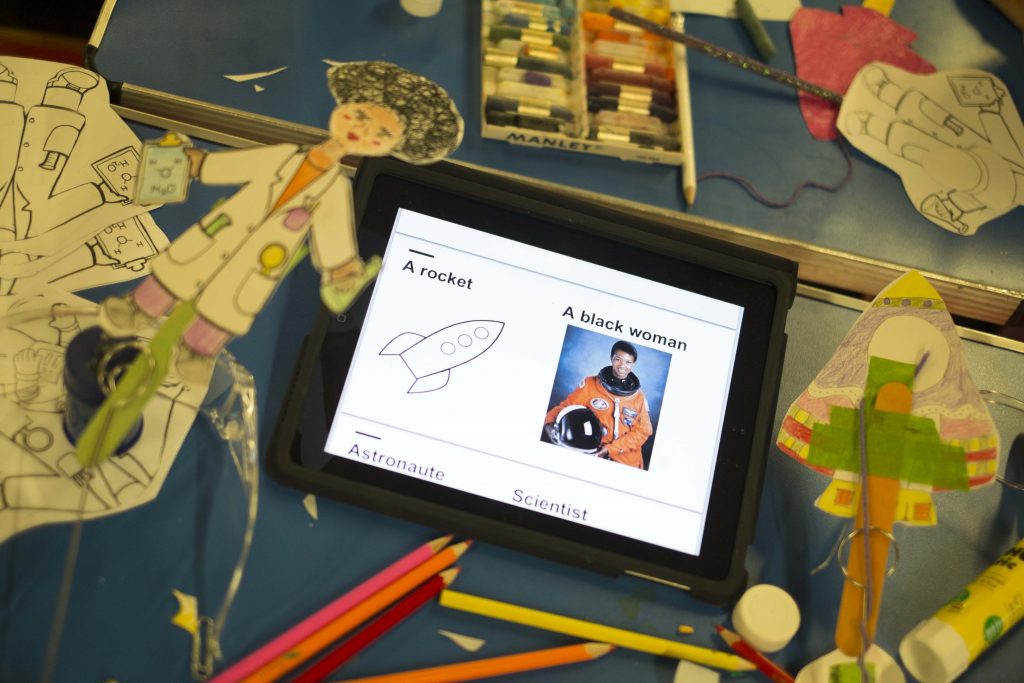

Thus, our workshops aim at introducing these important historic women and their achievements to participants, who then use art – either by making puppets, clay mini statues, carnival costumes or banners – to visualise and even become part of these stories. We believe that something as ‘simple’ as children creating puppets of black women dressed as astronauts or scientists can help change those children’s perceptions. Our goal is for them to associate those careers and achievements not only with white men.

We have to rethink history. We have to question it and change paradigms to make our national history more inclusive. It might indeed be sad, or unfair, that we must still celebrate Black History Month, or Women’s History Month for that matter. However, the stories that Black History Month reveals continue to remain outside of our national story and identity. So until this changes and everyone, regardless of social class or background, is aware of them, Black History Month remains relevant and needed.